The future of accessible transportation

Avivi is a service that aims to direct this innovation towards making lives better for those disconnected from major transit arteries, thus leveraging it to do the most good. In this seven-week exploration, we developed the seeds of a service that brings autonomous vehicles to the public in a way that is sustainable, affordable, and dependable.

Brief

Context

Spring 2018 at Carnegie Mellon University

Team

Timeline

Tools & Methods

InDesign

Illustrator

Fusion 360

Pen + Paper

My Role

How might we...

...leverage autonomous vehicle technology to bridge the transportation gap sustainably, affordably, and dependably?

The Challenge

Transportation is now the top contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. This, coupled with growing urban populations and the fact that nearly 90% of U.S. commuters use personal vehicles as their primary mode of transportation, ultimately makes driving unsustainable in many burgeoning metropolises. Cities are looking for low-impact ways to move people around that leverages existing infrastructure to keep implementation realistic.

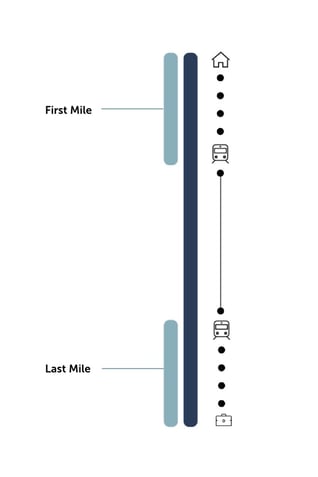

Here, we saw a design opportunity in solving the last mile problem. Could a service centered around autonomous vehicles be implemented in a way that is convenient enough to overtake personal vehicle use, and solve transit issues, rather than exacerbating them?

The Outcome

Avivi is a service that aims to direct this innovation towards making lives better for those disconnected from major transit arteries, thus leveraging it to do the most good. In this seven-week exploration, we developed the seeds of a service that brings autonomous vehicles to the public in a way that is sustainable, affordable, and dependable.

Public Partnership-Led Autonomous Transit

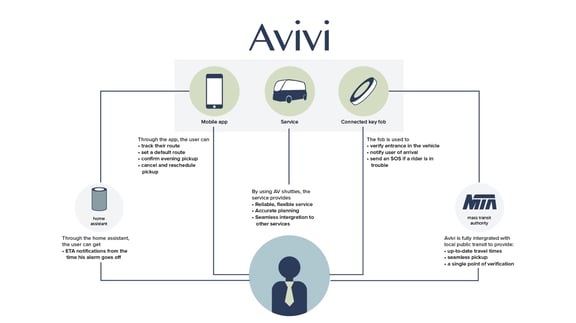

What makes Avivi unique is its public-private partnership—a reliable approach to solving the last-mile problem can only work if major transit arteries are not clogged by low-capacity vehicles.

Avivi integrates public transit information into the service to allow for reliable route planning and minimal wait times at transfer points.

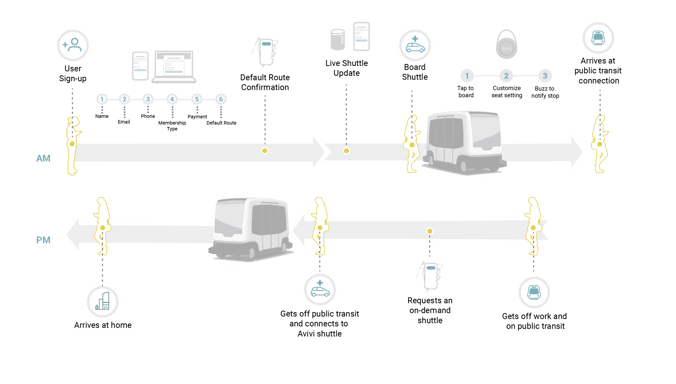

Fixed Mornings, Flexible Evenings

As a commuter service, Avivi adapts to commuter patterns at different times of day. In the mornings, commuters must arrive regularly at a set time. Commuter pass holders can reserve a daily ride on Avivi shuttles to ensure they arrive at work on time.

At the end of the day, however, patterns tend to shift due to hobbies, overtime, and errands. To answer this call, Avivi uses a different pattern in the evenings, where commuters call vehicles on demand. Avivi shuttles are deployed when a critical mass of riders is reached, but with a comfortable maximum wait time.

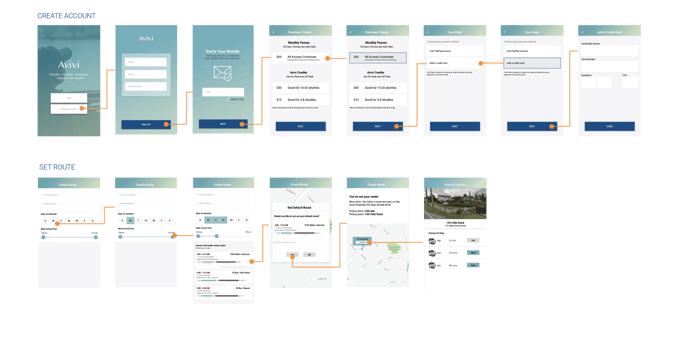

Mobile App

The primary point of communication with the service is the app. Here, users can select their plans, plan and track routes, and receive notifications for most convenient connections.

Avivi Key

The Avivi key acts as a secondary check-in device to keep commuters safe. It is also used in-shuttle to set personalization settings.

Our Process

Brainstorming

We came together as a team for this project with mutual interest in creating something for social good. During our early meetings, we discussed what current disruptive technologies have potential to have the most positive effects on communities.

Autonomous vehicle technology evokes a range of excitement and fear among the public. We set out to design a use for autonomous vehicles that makes lives better—not only for those who could feasibly own the technology, but for communities at large.

Defining Stakeholders

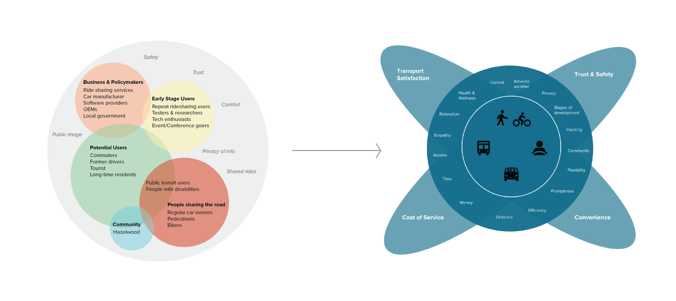

To get ideas flowing, we built a territory map to discover shared concerns among stakeholders in the commuting space. We quickly realized that visualizing these shared concerns would be difficult, since many concerns were shared over different assemblages of stakeholders.

Our final territory map reflected the fact that these lines of concern were blurred, by showing a group of users in the center, surrounded by their granular concerns, with overarching themes in the last layer.

Survey

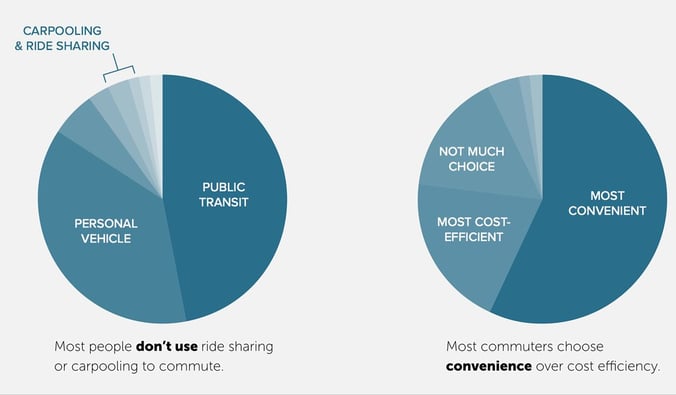

We followed this up with two surveys sent to over 70 participants, asking them about their various attitudes and experiences with commuting and autonomous vehicles.

In the free text entry portions of our survey, we learned that users who default to public transit like it because, at its best, it’s a time to spend enjoying solitude uninterrupted by the stresses of driving. At worst, commuting by public transit is frustrating due to its unpredictability, vulnerability to delays, and pains of connecting from one’s home.

This told us right off the bat that seamlessness is the most attractive selling point for public transit, and if we can amplify that through autonomous vehicles, coupling it with its inherent strengths, we’d have a decent service. As one survey respondent put it:

“I’m happiest when I don’t have to think about my commute and it just goes well.”

Exploratory Research

Competitive Analysis

We researched five different ride sharing & transit services in detail in order to determine our service model. For each of the companies, we focused on identifying the unique service value, sign-up process, payment models and service structure. In addition to these private companies, we also did research on pilot AV services, like the Mcity Driverless Shuttle at the University of Michigan and May Mobility AV Shuttles in Detroit.

This research was ongoing throughout the design process, but what it ultimately helped us do was determine our own value proposition. Much like Chariot, we wanted to have different types of payment options (All Access vs Credits) to make our service flexible, yet efficient.

We also found interest in how Via licenses their technology to local transportation authorities. In combination with our scenarios and exploratory research, competitive analysis helped us lay a foundation for how we wanted to serve our user.

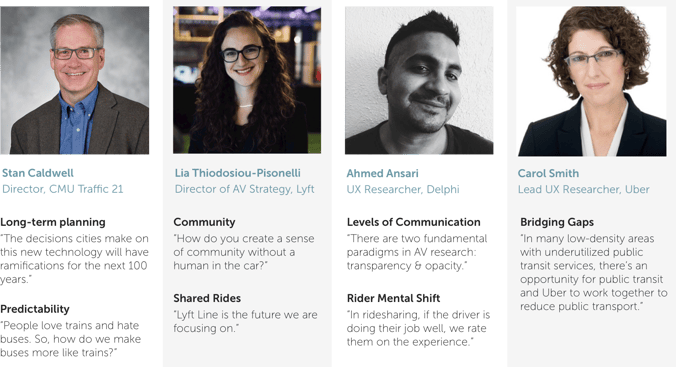

Expert Interviews & Secondary Research

What was truly pivotal in our development were the interviews we were fortunate enough to conduct with professionals at the forefront of autonomous vehicle research. While many couldn’t discuss their research explicitly, they helped us to begin asking the questions that are driving much of the research happening today.

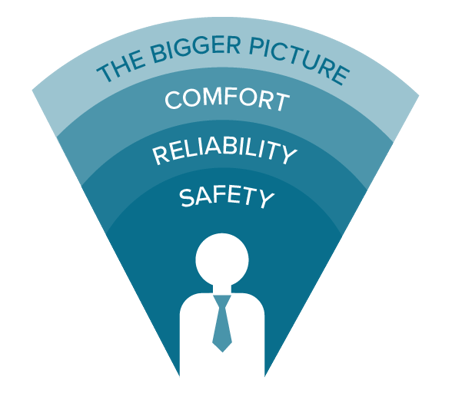

Design Imperatives

This wealth of information from stakeholders and experts, along with secondary research, helped us to formulate the design imperatives that guided us through the development of our service.

Our service must prioritize safety.

Our service should consider reliability and comfort.

Our service could address the bigger picture.

Concept Development

This wealth of information from stakeholders and experts, along with secondary research, helped us to formulate the imperatives that guided us through the development of our service.

We developed four unique personas and scenarios that helped us think about what an autonomous ride-sharing service might look like for people of different income levels, different living situations and commuting needs.

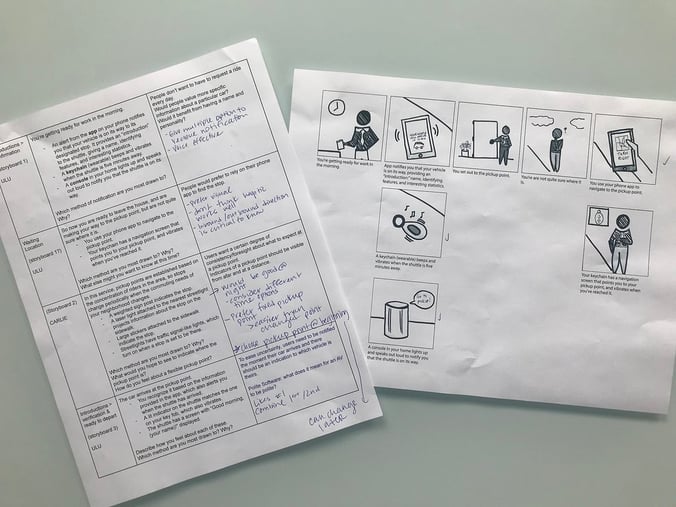

We experimented with voice, visual and tactile features – and how they would fit into a system that spanned home, vehicle and work.

Going into scenario-building, we had already scoped in on serving commuters, but had not decided on the type of service we would provide (i.e. shuttle vs on-demand ridesharing vs. private end-to-end service). This exercise was in many ways challenging because it was our first attempt at trying to make sense of unique user experiences and feasible service models at the same time.

Going into testing, we decided to try a branching storyboard model to gut check different components.

Speed Dating

We tested with prospective users (namely, commuters who own a car, but do not use it to commute to work).

This helped us to discover not only which touchpoints would be most useful to our target audience, but recurring themes that would help us define what they would want out of our service overall.

What we learned is that users wanted to be able to go on autopilot (a best case scenario when riding public transit currently) and be able to enjoy solitude (the greatest affordance of commuting by car), and just about everything else was superfluous. Anything we created would have to facilitate those things in order to resonate with our target users. Relating back to our imperatives, this translated to a slight reprioritization:

Comfort: Comfort is ease. On short commutes, people value “me time” over added features.

Reliability: To users, reliability means being able to get to work everyday at a certain time, but having flexibility on the way home.

Safety: In the context of a service, people are less concerned about safety then they are about ease.

Refinement

This all led us to build a multiple-touchpoint system, centered around the service itself.

Reflections

What was helpful

This is a vast research landscape at the moment, and it was a lot to take on for a six-week project. We were lucky to conduct it at Carnegie Mellon and in Pittsburgh, because it afforded access to conversations with people who could help frame the potential of AVs in a way that sifting through research papers alone could not. Our solution at its core is quite simple, but it only works with autonomous technology, and their insight was essential for framing it properly.

What has the most potential

Based on research and testing, we believe that the service model, with a core customer base using the service in a scheduled manner supplemented by users who fill empty seats at the last minute, is a very economically sound use of AVs and can be of help to a wide range of users. This essentially is the model that many existing train services use, with both reserved and unreserved seats, and we see the potential for applying a similar model to help sustain a commuting transit service that gets regular scheduled usage.

Given more time…

We would have further developed our service-scape in three key areas. First, we would have developed an in-car screen component to communicate safety measures to the riders. We didn’t develop this piece for the presentation because we received mixed feedback around this component during user testing. We also felt like there was more research to be done around when to provide visual feedback to the riders.

Second, given more time, we would have done more testing and prototyping on the SOS feature of the Avivi key. We explored this feature as a tool for interpersonal safety but ultimately didn’t feel like it was an essential element of our user’s system. Third, we would like to test more users in order to consider features and comfort levels for different lengths of commute.